The Sword Outwears Its Sheath: Love, Loss, and Meaning in the Epic of Gilgamesh

What does it mean to love when every cherished bond faces the absolute certainty of loss? In the epic of Gilgamesh, we encounter timeless themes of love and mortality.

You’re reading Galloquium, an extended meditation on creating meaning and achieving mastery in life.

The sword outwears its sheath,

And the soul wears out the breast,

And the heart must pause to breathe,

And love itself have rest.

— Lord Byron

As we contemplate the great sweep of human experience, we are reminded that love, whether romantic or platonic, is always destined to end—by death, by distance, or by the quiet erosion of time. What then does it mean to love something that you know will one day be lost? This question, as ancient as humanity itself, has perplexed philosophers, poets, and kings. It is the very question at the heart of the epic of Gilgamesh, the oldest surviving written story. Gilgamesh, the mighty king of Uruk, wrestles with what it means to live fully knowing that everything he cherishes will fade.

At its core, the story of Gilgamesh explores the tension between mortality and the search for meaning in life. Through the lens of Gilgamesh's friendship with Enkidu and his quest for immortality, the tale grapples with themes that remain deeply relevant today. It is remarkable how this ancient tale, written thousands of years ago in a world so different from our own, can capture the complexities of the human condition with such raw power.

The Transformation of Gilgamesh

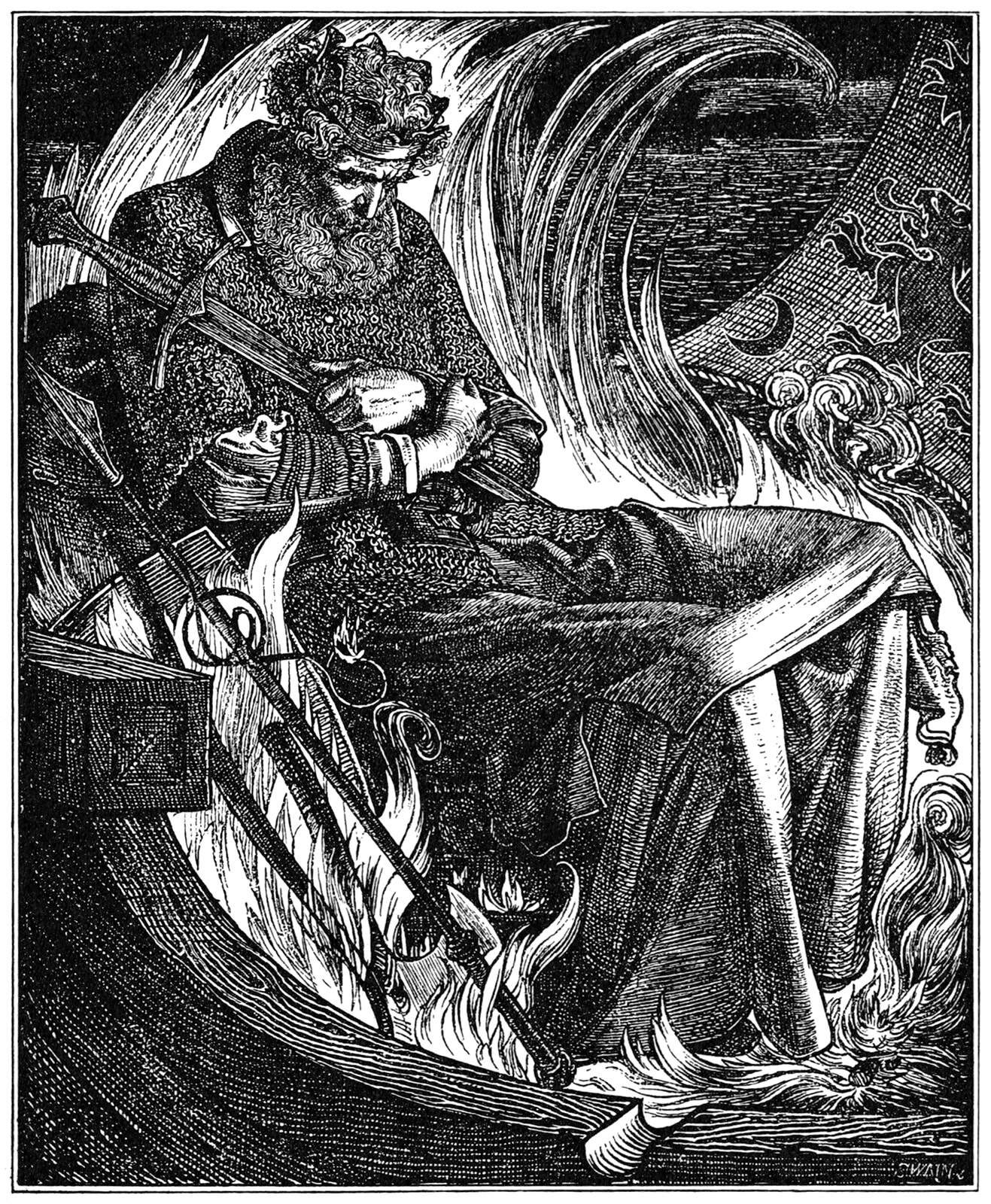

Gilgamesh is introduced as a figure of immense power—an all-powerful king who exploits his people without regard for their suffering. His rule is tyrannical, his desires unchecked, and his people suffer under his harsh leadership. In response, the gods create Enkidu, a wild man from the wilderness, to challenge Gilgamesh's arrogance. Their initial confrontation is intense, but it forges an inseparable bond between them—a friendship that becomes the heart of the epic, transforming Gilgamesh from a tyrant into a more human figure. Through this relationship, the central themes of love, loss, and meaning begin to unfold.

The bond between Gilgamesh and Enkidu transcends the physical, touching the spiritual. C.S. Lewis once wrote, “To love at all is to be vulnerable.” In loving Enkidu, Gilgamesh opens himself to a new kind of vulnerability—one he never anticipated. Yet their brotherhood—like all forms of love—is impermanent. As the epic progresses, it becomes clear that the joy of their bond must inevitably give way to sorrow.

Together, the pair face grand challenges, from defeating the monstrous Humbaba to slaying the Bull of Heaven sent by the goddess Ishtar. But their victory over the Bull of Heaven comes at a steep cost. The gods decree that Enkidu must die as punishment for their hubris. His death devastates Gilgamesh, whose grief is visceral and profound. “My friend, the great wild bull, is lying down,” he laments. “My friend Enkidu, whom I loved, is dead.”

His mourning is not just a response to loss but a testament to the depth of their bond. If the bond between Gilgamesh and Enkidu had been shallow, Gilgamesh’s mourning would not have been so overwhelming. “For love is as strong as death,” we read in the Song of Solomon, “its jealousy unyielding as the grave.”

Grief is Love Persevering

Gilgamesh’s mourning for Enkidu reminds us that grief is not the opposite of love; it is love in another form, one that lingers long after the physical presence of the beloved is gone. The pain of losing someone we cherish is a testament to the depth of our connection. This sentiment is echoed in the words of the poet Mary Oliver:

To live in this world

you must be able

to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it

against your bones knowing

your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go,

to let it go.

Enkidu’s death shatters Gilgamesh’s worldview, forcing him to confront for the first time the reality that death spares no one—not even kings. In his anguish, Gilgamesh embarks on a desperate quest for immortality, determined to escape the fate that has claimed his friend. In one of his most poignant moments, he cries out, “Shall I, after I have roamed hither and thither across the expanse of the wilderness as a wanderer, lay my head down within the bowels of the Earth, and slumber throughout the years forever and ever? Let mine eyes behold the Sun, and be sated with the light.”

The Illusion of Immortality

Throughout his journey, Gilgamesh encounters wise figures who counsel him on life’s impermanence. The tavern keeper Siduri advises him, “As for you, Gilgamesh, let your stomach always be full. Be of good cheer each day and each night. Fill each day with merriment. With dancing and rejoicing, let every day abound... Cherish the little child who holds your hand. Bring joy to the loins of your wife. This, then, is the work of man.” This call to immerse ourselves in the present is not an invitation to hedonism, but a reminder that life’s beauty is found in small, daily acts of love, joy, and connection.

Despite receiving this wisdom, Gilgamesh presses on, eventually meeting Utnapishtim, the survivor of a great flood who was granted eternal life by the gods. Utnapishtim explains that immortality is a gift reserved for the gods, and that “It is not given to men to live forever. Numbered are their life-days, and all their exertions are but like the wind.”

Utnapishtim’s words are a harsh truth. Despite Gilgamesh’s power, despite his accomplishments and his desire for eternal life, he cannot escape death. Everything—his military victories, his reign as king, his very life—is temporary.

Love is All that Will Remain

Grief is the shadow that follows love, inseparable from its light. This echoes Kahlil Gibran’s reflection in The Prophet: “The deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you can contain.” Just as the beauty of a sunset is magnified by the knowledge that it will soon fade, so too is love heightened by the awareness that it is impermanent. Trying to hold on to it forever is as futile as Gilgamesh's quest for immortality. This fleeting nature does not cheapen joy or love—it intensifies them.

The epic concludes with Gilgamesh’s return to Uruk, not as the immortal hero he once sought to be, but as a man who has come to terms with his own mortality. His quest for eternal life ends not with the discovery of a fountain of youth, but with something far more significant: wisdom. His journey across the world in search of immortality brought him to the realization that immortality is not found in avoiding death, but in the legacy one leaves behind.

Like Gilgamesh, we too often struggle with the knowledge that everything we hold dear will eventually be lost. But what Gilgamesh learned—and what we are invited to learn with him—is that it is precisely because life is temporary that it must be savored. As Seneca wrote, “It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it.” Gilgamesh’s story reminds us to cherish each moment, to seize joy wherever we find it, because it is these ephemeral experiences that give life its profound worth.

This lesson is as relevant today as it was in ancient Mesopotamia. We live in a world that tries to convince us that our professional achievements, relationships, and even physical beauty can last forever. Yet, as Gilgamesh’s journey reminds us, these things are inherently transient. The walls of Uruk may endure for a time, but even they will eventually crumble. What remains, in the end, is the impact we have on others—the relationships we build and the love we share.

Embracing Life’s Impermanence

Despite his heroic efforts, Gilgamesh never finds the immortality he seeks. Instead, his journey concludes with the realization that immortality was never the answer—it is life’s impermanence that gives it meaning. If we lived forever, would our actions carry the same weight? Would we value love and friendship in the same way? Probably not. It is the fleeting nature of our experiences that makes them precious.

Jason Isbell’s song If We Were Vampires resonates even more in this context:

If we were vampires and death was a joke

We'd go out on the sidewalk and smoke

Laugh at all the lovers and their plans

I wouldn't feel the need to hold your hand

Maybe time running out is a gift

I'll work hard 'til the end of my shift

And give you every second I can find

And hope it isn't me who's left behindIt's knowing that this can't go on forever

Likely one of us will have to spend some days alone

Maybe we'll get forty years together

But one day I'll be gone

Or one day you'll be gone

It’s knowing that this can’t go on forever that makes every moment so valuable. Gilgamesh’s story urges us to stop chasing illusions and instead focus on what truly matters—not the length of our lives, but the depth of our love and the richness of our experiences. It is not the years we are given, but how fully we live them that will ultimately define our lives.

Love is not diminished by its impermanence; it is made more powerful by it. As we journey through life, we will know both joy and sorrow, but in the end, it is love that endures. And as Gilgamesh learned, that is enough.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it.

References and Further Reading

Although there are more recent translations, I recommend Gerald J. Davis’ rendering of Gilgamesh. All quotes are taken from this translation. Stephen Mitchell’s translation is also excellent.

Robert Silverberg also wrote a novelization of the epic that attempts to ground the more fantastic aspects in reality. Not required reading by any means, but I personally found it useful for understanding some of the context around archaic practices mentioned in the epic.

The Lord Byron quote is from his poem So We’ll Go No More a Roving.

C.S. Lewis wrote The Fours Loves. The section on friendship is particularly relevant to Gilgamesh and Enkidu.

The Mary Oliver quote is an extract from her poem In Blackwater Woods. Originally published in her collection American Primitive and also available to read online.

Please read Kahlil Gibran’s masterpiece The Prophet immediately. It doesn’t matter how many times you may have read it before, it’s never enough.

The quote, “It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it” is from Seneca’s essay On the Shortness of Life, written around AD 49. It reflects on the value of time and the importance of using it wisely.

Jason Isbell’s song If We Were Vampires speaks for itself.