The Problem with Happiness

Happiness cannot be found by pursuing it. It comes as a side effect of devoting yourself to something greater. You have to let it happen by not caring about it.

You’re reading Galloquium, an extended meditation on creating meaning and achieving mastery in life.

We often imagine happiness as a tranquil state of being, where problems are magically absent and everything runs smoothly—kind of like floating in a pool on a summer day with no deadlines, no drama, and no unexpected splashes. But here’s the thing: spend too long in that pool, and you’ll get pruney and bored. In fact, a life without problems wouldn’t just be dull—it would be unbearable. A person without any problems, as it turns out, can’t be happy for long.

That’s because happiness doesn’t come from having no problems. It comes from having the right problems.

The Right Kind of Problems

Now, don’t get me wrong. Some problems are objectively terrible. We’re talking about the big ones—hunger, poverty, loss of a loved one, discrimination. Only a masochist would want those kinds of challenges. As much as I’m a fan of personal growth, I’m not suggesting you need to be the target of discrimination or be struggling to make ends meet in order to find meaning in life. That's a different kind of misery altogether.

But let’s think about the everyday problems—the kind we do need. Freud claimed that people seek pleasure above all else, but Viktor Frankl, the brilliant Austrian psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, disagreed. Meaning, he believed, was our true motivator, and without it, life becomes empty—no matter how many pleasures we pile on.

In his book Man’s Search for Meaning, Frankl argues that happiness isn’t really what we’re after at all. What we actually seek is meaning. And when we can’t find meaning, we use pleasure as a stand-in, a temporary escape from the void of meaning.

This is why a life filled with all the comforts—food, entertainment, relaxation—quickly turns into a nightmare of boredom. Studies show that people with unlimited access to pleasures often find themselves restless and dissatisfied. Research has shown that individuals who feel a strong sense of purpose report higher levels of happiness and life satisfaction. A 2021 study found that as people increased their sense of purpose, their well-being—and even their health—improved.

Interestingly, the research also suggests that having too much free time, without any meaningful activity to fill it, can lead to boredom and aimlessness. People who find themselves with excessive leisure often fare better when they use that time for purpose-driven activities.

In short, we’re wired to need a sense of meaning, something greater than ourselves to fight for. If we don’t have it, we’re left feeling adrift, no matter how much pleasure or comfort we surround ourselves with.

The Paradox of Pursuing Happiness

So here’s the kicker: if you aim for happiness directly, you’re probably going to miss it. Frankl said it best:

“Don’t aim at success—the more you aim at it and make it a target, the more you are going to miss it. For success, like happiness, cannot be pursued; it must ensue, and it only does so as the unintended side-effect of one’s dedication to a cause greater than oneself or as the by-product of one’s surrender to a person other than oneself. Happiness must happen, and the same holds for success: you have to let it happen by not caring about it.”

It’s counterintuitive, right? We spend our lives trying to chase happiness, thinking we’ll find it on the other side of a job promotion, a new relationship, or a fancy vacation. But happiness is sneaky. It doesn’t show up when you’re looking for it. Instead, it sneaks in through the back door, while you’re busy focusing on something else—a project you care about, a person you love, or a problem worth solving.

Sisyphus and the Art of Struggle

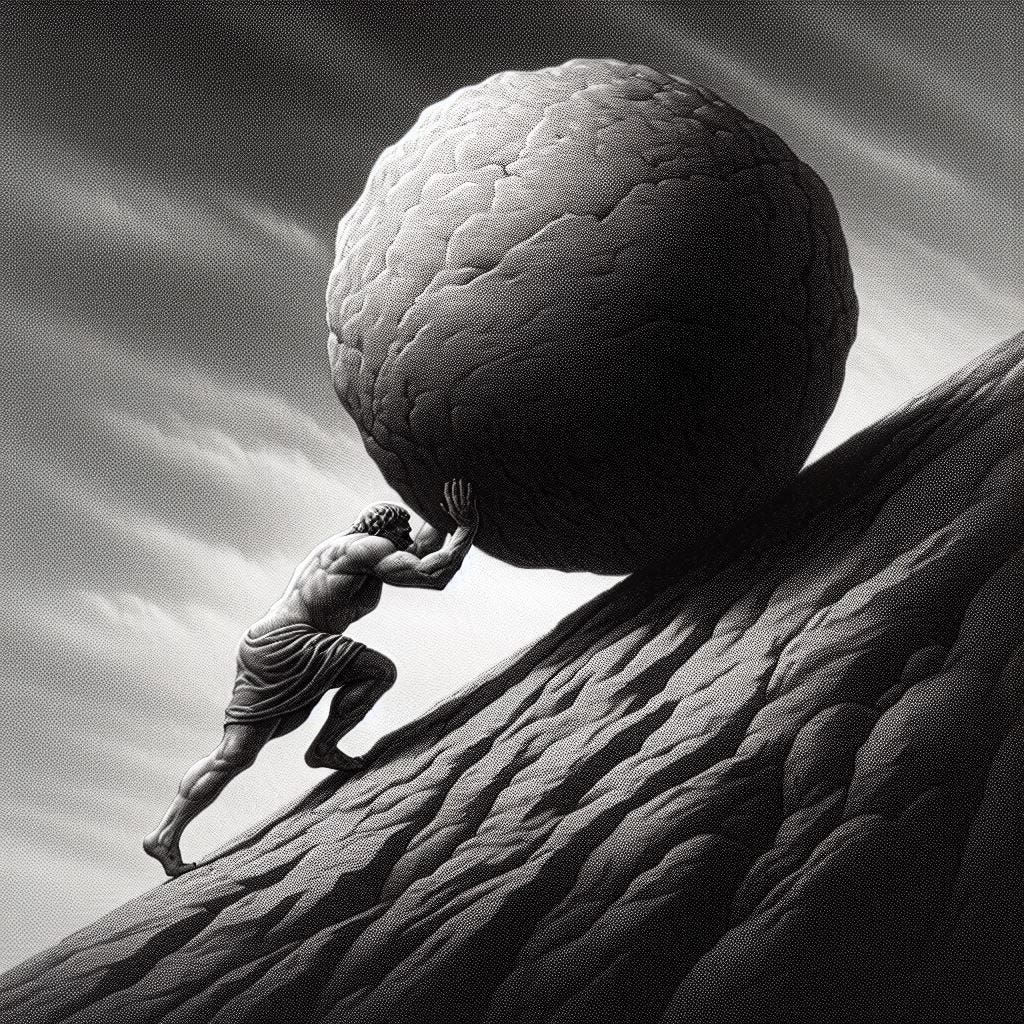

This idea isn’t new. In fact, the ancient Greeks gave us a perfect metaphor for this in the myth of Sisyphus. Poor Sisyphus was condemned to roll a boulder up a hill for eternity, only to watch it roll back down each time he reached the top. On the surface, it’s a story of futility, an eternal struggle with no resolution. But Albert Camus, the existential philosopher, gives us a surprising twist. He tells us to “imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Wait, what? How could someone condemned to an endless, pointless task be happy? According to Camus, it’s not the outcome of Sisyphus’s struggle that matters—it’s the struggle itself. Life’s challenges aren’t meant to be "solved" once and for all. The struggle itself is where we find meaning. The act of pushing that boulder, day after day, is what gives his life meaning. It’s a dark twist on the idea, but the point holds: we find meaning in the striving, not necessarily in the destination.

Why We Need Problems

Think about it: when you’re completely at rest, with nothing challenging on your plate, life starts to feel...stagnant. Sure, lying on the beach is fun for a few days. But after a while, don’t you start feeling an itch to do something? To solve something? It’s not that we want life to be hard, but we need some friction. Stagnation is just death in disguise, as surely as standing water breeds mosquitoes.

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi coined the term "flow" to describe the state of being fully immersed in a task, where challenge and skill are perfectly balanced. This state of flow is when we’re happiest, when we’re so focused on a problem that we lose track of time and forget to check our phones. We don’t experience this kind of fulfillment when things are too easy or when there are no challenges. We experience it when we’re engaged in solving a meaningful problem—something that pushes us, but not to the point of breaking.

So, What’s the Right Problem?

Finding the “right” problem isn’t a one-size-fits-all affair. Some of us thrive on intellectual challenges, while others need to pour their energy into relationships or physical accomplishments. But one thing is universal: the sense that we’re working toward something meaningful, something that makes us feel like we’re growing, learning, or making an impact. A person who devotes their energy to a problem worth solving is someone who wakes up with purpose—even if their days are filled with hard work and struggle.

And this is where Frankl’s wisdom rings true. “Happiness must happen.” It’s not a target you aim for, but a by-product of solving meaningful problems. So, if you ever find yourself wondering why you’re unhappy despite having everything you need, ask yourself: What’s my problem? And I mean that in the best way possible.

Sisyphus had his boulder. What’s yours?

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it.

References and Further Reading

Viktor Frankl’s quote, as well as the idea that what people really need is meaning, not pleasure, comes from his book Man's Search for Meaning. Originally published in 1946, this book explores the human pursuit of meaning, using Frankl’s experiences in Nazi concentration camps to illustrate the importance of finding purpose in life.

The 2021 study referenced was conducted by Tim D. Windsor et al. It can be read in full here, or in a more accessible summary.

Camus’ spin on the story of Sisyphus is explored in his essay The Myth of Sisyphus, first published in 1942. In this philosophical essay Camus explores absurdism and argues that the struggle toward the heights is itself enough to fill a man's heart.

The idea of flow was introduced by Csikszentmihalyi in the 1990 book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. He defined flow as a state of being fully immersed in a task, where challenge and skill are balanced, leading to a feeling of happiness and fulfillment.

Freud's idea that people are motivated by the desire to seek pleasure and avoid pain is explored at length in his 1920 text Beyond the Pleasure Principle.