Finding Peace Through Expanded Horizons

Sometimes it feels like the world is coming to an end. We face many serious existential challenges. But despair and hopelessness are caused by limited vision. The solution is to expand our horizons.

"When the world is storm-driven and the bad that happens and the worse that threatens are so urgent as to shut out everything else from view, then we need to know all the strong fortresses of the spirit which men have built through the ages. The eternal perspectives are being blotted out, and our judgment of immediate issues will go wrong unless we bring them back." — Eric Greitens

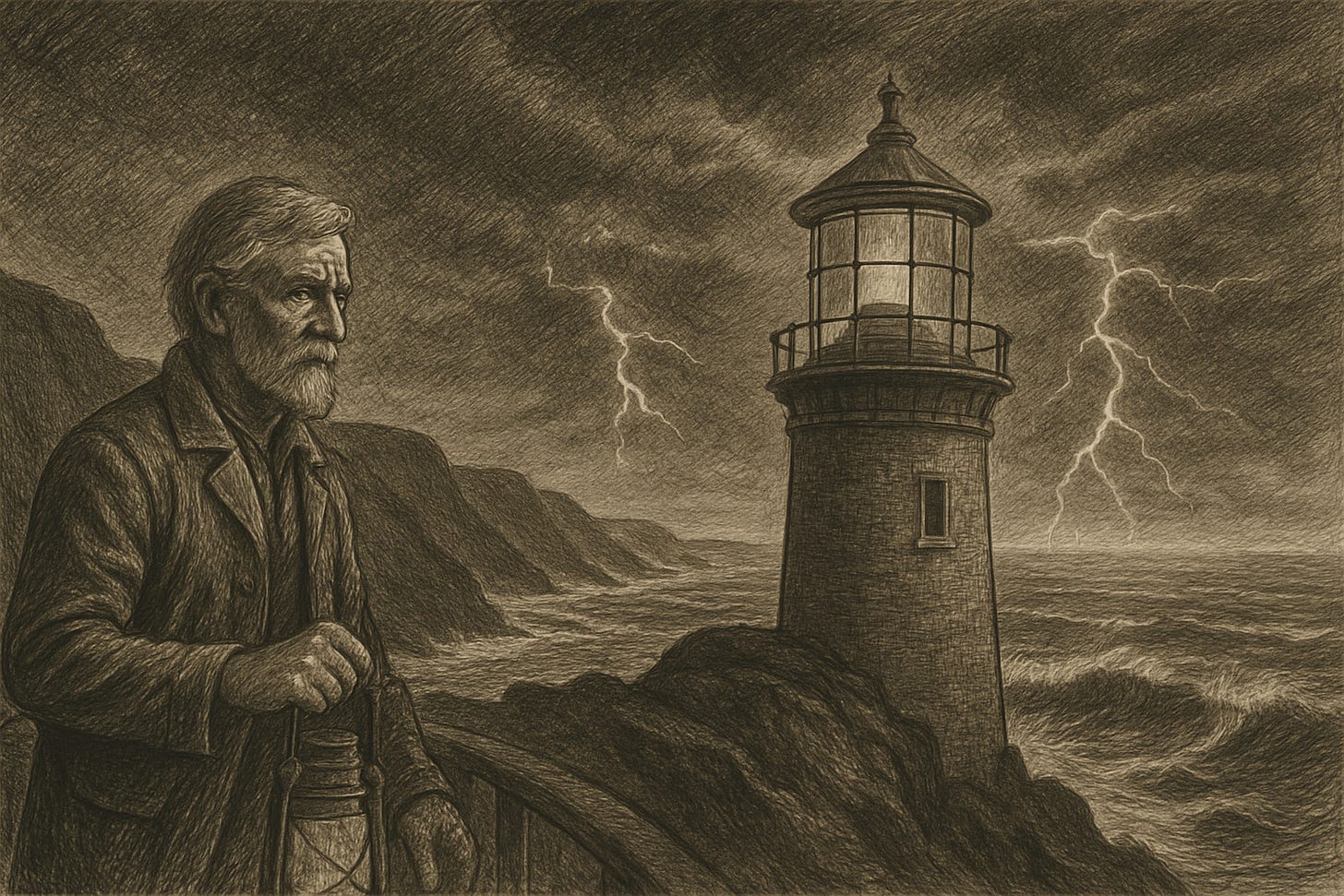

The lighthouse keeper stands at his post, watching as storm clouds gather on the horizon. The sea begins to churn, waves crashing against the rocky shore with increasing violence. As darkness falls and rain lashes against the windows, his world contracts to the small circle of light surrounding his tower. In this moment, it is easy to believe that the storm encompasses all of existence—that there is nothing beyond the howling wind and churning waters.

But the keeper knows better. He has weathered countless tempests from this very spot. His logs chronicle decades of nature's fury, followed invariably by calm seas and clear skies. The charts on his wall map coastlines shaped by centuries of such cycles. And the light he tends has guided ships through treacherous waters for generations before him and will continue long after he is gone.

His peace amid chaos comes not from denying the storm's destructive potential, but from understanding its place in a much larger pattern—a pattern visible only when one's gaze extends beyond the immediate horizon.

We, too, stand at our posts amid gathering storms. Political polarization, climate change, technological disruption, economic uncertainty—the list of existential threats seems to grow with each passing day. Media cycles bombard us with evidence of impending doom, and social networks amplify our collective anxiety. In such moments, our perspective naturally contracts. We become temporal myopics, seeing only the crisis at hand and forgetting that we stand in a long continuum of human experience.

This myopia breeds despair. When we perceive the present crisis as unprecedented and all-encompassing, we lose faith in our capacity to endure and overcome. But what if the antidote to this despair lies not in fixing every problem immediately, but in expanding our horizons—looking backward to the wisdom of the past and forward to the possibilities of the future?

Anchors in the Past: The Fortresses of Human Resilience

History offers us a paradoxical comfort: we are not the first to believe the world is ending. Each generation has faced its own apocalyptic scenarios, its own seemingly insurmountable challenges. The Romans watched their empire crumble, medieval Europeans buried one-third of their population during the Black Death, the World Wars of the 20th century claimed tens of millions of lives. Each of these moments must have felt like the end of history to those living through them.

Yet humanity persisted. More than that—we adapted, recovered, and often flourished in the aftermath of disaster. The Black Death was followed by the Renaissance. The devastation of World War II gave birth to unprecedented international cooperation and human rights frameworks. Time and again, what appeared to be civilization's death knell proved instead to be painful but transformative transition.

"Be joyful though you have considered all the facts." —Wendell Berry

This historical perspective doesn't diminish the gravity of our current challenges. Climate change poses genuine existential threats; political polarization can indeed unravel democracies; technological disruption carries real risks. But history reminds us that humans have confronted existential threats before and found ways not just to survive but to create new possibilities from the ashes of catastrophe.

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche captured this capacity in his concept of amor fati—the love of fate—which embraces life's inevitable sufferings as opportunities for growth and transformation. Marcus Aurelius, ruling a Roman Empire beset by plague, invasion, and betrayal, wrote meditations that continue to offer solace precisely because the challenges he faced resonate across millennia: "You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength."

The wisdom of the Stoics feels particularly relevant in our anxious age. As Seneca advised during Nero's turbulent reign: "We suffer more often in imagination than in reality." His counsel to distinguish between what we can and cannot control provides a practical framework for navigating uncertainty: "The chief task in life is simply this: to identify and separate matters so that I can say clearly to myself which are externals not under my control, and which have to do with the choices I actually control."

These voices from the past are not distant academic curiosities but, to borrow a phrase from Eric Greitens, fortresses of the spirit—proven shelters that have weathered history's greatest storms. By studying them, we discover that our anxiety, our fear, our sense of standing at history's precipice, are timeless human experiences. And in discovering this continuity with the past, we find something precious: the knowledge that others have stood where we stand, felt what we feel, and nevertheless found paths forward.

As Chuck Klosterman observes, "The practical reality is that any present-tense version of the world is unstable. What we currently consider to be true—both objectively and subjectively—is habitually provisional." This insight, rather than undermining our confidence, should liberate us from the tyranny of the present moment. The certainties and crises that consume us today will appear very different when viewed through the lens of historical perspective.

How Historical Wisdom Transforms Our Present

What happens, physiologically and psychologically, when we encounter these fortresses of the spirit? How exactly does reading Marcus Aurelius or studying how previous generations endured their own apocalyptic scenarios transform our relationship with present challenges?

The answer lies in part in what psychologists call cognitive reappraisal—the process by which we change how we think about a situation, thereby changing our emotional response to it. When we learn that Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother, "Looking at the stars always makes me dream," while confined in an asylum, something profound shifts in our own neural pathways.

Neurologically, exposure to stories of resilience activates brain regions associated with meaning-making and emotional regulation. As we internalize these narratives, our default interpretations of adversity begin to change. The psychologist Viktor Frankl, who survived Nazi concentration camps, observed this phenomenon with remarkable clarity: "When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves." This capacity for reframing—for seeing suffering as meaningful rather than merely painful—becomes available to us through the documented experiences of those who have demonstrated its power.

Psychiatrist and trauma specialist Bessel van der Kolk explains the mechanism: "Being able to feel safe with other people is probably the single most important aspect of mental health; safe connections are fundamental to meaningful and satisfying lives." Historical figures who weathered great crises become these "safe connections" across time—proven guides who assure us that the path, though difficult, is walkable.

The power of storytelling lies in its ability to transmit resilience strategies that have sustained humanity through its darkest chapters. Those who preserve and share wisdom across generations serve as essential cultural bridges, ensuring that hard-won insights aren't lost to time.

When I first encountered James Baldwin's assertion that "Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced," it altered how I understood both acceptance and action. Fortresses of the spirit provide us with these transformative frameworks—ways of seeing that simultaneously acknowledge reality while revealing possibilities invisible to the panicked or despairing mind.

The power of these perspectives lies in their tested nature. Unlike untried theories, they have endured history's crucible. They have sustained individuals through circumstances often far worse than our own. And in doing so, they offer not just comfort but practical wisdom about how to navigate toward meaningful action without being paralyzed by despair or delusions of omnipotence.

This historical wisdom doesn't just help us understand the past—it creates a foundation for how we might approach the future. By seeing how individuals and societies have navigated previous existential threats, we develop both humility about our present challenges and confidence in the human capacity to adapt and transform. With this grounding in tested resilience strategies, we can more thoughtfully extend our vision forward in time.

Extending Our Gaze: The Liberation of Future Thinking

If the past provides anchors for our storm-tossed spirits, the future offers wings. Looking ahead—not just to next week or next year, but to decades and centuries to come—fundamentally alters how we experience present difficulties.

Remember Y2K? As the millennium approached, serious commentators warned of potential civilizational collapse when computer systems failed to transition properly to dates beginning with "20" instead of "19." Billions were spent preparing for this digital apocalypse. And when January 1, 2000, arrived? A few minor glitches quickly resolved. Today, Y2K serves as a humbling reminder of how threats that loom catastrophically large in the present often shrink to footnotes in the broader narrative of human progress.

This patient perspective doesn't absolve us of responsibility for action, but it does release us from the paralyzing anxiety of believing that everything depends solely on us, right now.

This is not to say our current challenges are similarly overblown. Many are genuinely serious. But extending our temporal horizon helps us distinguish between what philosopher Emerson might call "the loud and the important"—between issues that dominate today's discourse and those that will genuinely shape humanity's future trajectory.

Consider how our perspective shifts when we contemplate what matters not just for our lifetime, but for our grandchildren's grandchildren. Suddenly, many political controversies that consume our attention reveal themselves as ephemeral, while quieter but more fundamental challenges—like how we steward knowledge, cultivate wisdom, and maintain human dignity—emerge as the essential questions worthy of our finest efforts.

This future-oriented thinking isn't merely about prioritization; it's about liberation. When we extend our perspective beyond our own lifespans, we're freed from the pressure to solve everything immediately. We can distinguish between problems that require urgent action and those that demand patient, generations-long commitment. We see ourselves not as the final chapter in human history, responsible for saving or dooming everything, but as links in a much longer chain—contributors to an unfolding story larger than ourselves.

As the poet Rainer Maria Rilke advised, "Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer." Some problems cannot be solved within a single lifetime or news cycle. They must be lived, explored, and gradually addressed over time. This patient perspective doesn't absolve us of responsibility for action, but it does release us from the paralyzing anxiety of believing that everything depends solely on us, right now.

Ecological philosopher Joanna Macy frames this beautifully in her concept of "active hope," which she distinguishes from both blind optimism and passive despair: "Active Hope is a practice... It involves three steps: first, a clear view of reality; second, identifying what we hope for in terms of the direction we'd like things to move in or the values we'd like to see expressed; and third, taking steps to move ourselves or our situation in that direction."

The Present Moment: Where Past and Future Meet

The lighthouse keeper does not ignore the storm raging around him. His historical knowledge and future thinking don't lead to passivity; they inform his present actions. He secures what needs securing, maintains his light with greater care, perhaps warns ships in the vicinity. But he does so without panic, knowing both the storm's proper context and his own limited but meaningful role within it.

Similarly, expanding our temporal horizons doesn't mean disengaging from present challenges. Quite the opposite. It means engaging more effectively, with the wisdom to distinguish between what we can change and what we must endure, between actions that serve short-term interests and those that contribute to longer arcs of progress.

The present moment is where we live and act. It's where past wisdom and future vision translate into tangible choices. The key is maintaining awareness of all three timeframes simultaneously—learning from history, contributing to the future, while fully inhabiting the now.

This three-dimensional temporal awareness characterizes humanity's greatest contributors. Lincoln preserved the Union not by fixating solely on immediate military victories, but by placing the Civil War within the broader context of America's founding principles while simultaneously envisioning a reunited nation. Gandhi's campaign of nonviolent resistance drew deeply from ancient religious teachings while maintaining a clear vision of a future independent India. In our own lives, we achieve our greatest impact when we similarly integrate historical perspective, future vision, and present action.

It is precisely this integration that allows us to fulfill what theologian Reinhold Niebuhr described in his famous "Serenity Prayer": "God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference." Without historical perspective, we lack the serenity that comes from knowing some struggles are perennial. Without future vision, we lack the courage to take meaningful action in the face of daunting odds. Without present awareness, we lack the wisdom to discern where our efforts are best directed.

The Responsibility of Expanded Vision

An expanded horizon does not absolve us of responsibility—quite the contrary. Once we see beyond the immediate crisis to the larger patterns of human experience, we incur an obligation to act with greater wisdom and purpose. As Václav Havel, who led Czechoslovakia from communism to democracy, reminds us: "Hope is definitely not the same thing as optimism. It is not the conviction that something will turn out well, but the certainty that something makes sense, regardless of how it turns out."

This deeper hope—rooted not in naïve optimism but in a commitment to meaningful action regardless of guaranteed outcomes—becomes possible only when we expand our temporal horizon. We act not because we are certain of success within our lifetime, but because we understand our role in a much longer human story.

The expanded vision I'm advocating isn't a prescription for passivity or an excuse for inaction. It's the foundation for more sustainable, meaningful engagement with the world's genuine challenges. When we understand ourselves as neither the first to face great trials nor the last who will work to address them, we gain both humility and courage—humility about the scope of what we alone can accomplish, and courage to make our necessary contribution nonetheless.

The present moment is where we live and act. It's where past wisdom and future vision translate into tangible choices.

Rabbi Tarfon, a sage of the Mishnah, captured this balance perfectly nearly two millennia ago: "It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either." This speaks directly to our modern predicament. We cannot fix everything at once, but we must do what we can, where we are, with what we have—not from a place of panic or despair, but from a grounded understanding of our place in time's continuum.

Amid today's storms, this integrated awareness offers something beyond mere resilience. It offers the possibility of genuine peace—not the fragile peace that depends on all problems being solved, but the deeper peace that comes from knowing our place in time's continuum. We need not carry the weight of all history on our shoulders. We are neither the culmination of human experience nor its final chapter. We are participants in a much larger story—tasked with playing our part well, but not responsible for writing the entire narrative.

Finding Peace Beyond the Storm

The storm that seemed all-encompassing from the lighthouse window eventually passes. The keeper steps outside onto the gallery and gazes across waters that still churn but no longer threaten. The air has that peculiar clarity that often follows tempests, allowing him to see farther than usual. On the distant horizon, faint but unmistakable, other lighthouses stand—some built centuries before his own, others erected within his lifetime. Each represents a human outpost against chaos, a commitment to guide those navigating treacherous waters. Together, they form a constellation of light stretching along the coastline—each keeper isolated in their tower yet part of something larger and more enduring than any individual.

Our own moment of clarity comes when we recognize that we too stand in such a constellation—connected to those who came before us, those who will follow, and those who, right now, tend their own lights amid different but equally challenging storms. This recognition doesn't eliminate the very real dangers we face, but it transforms how we experience them.

When we expand our horizons beyond the present crisis, we discover something remarkable: the possibility of contributing meaningfully to human flourishing without bearing the impossible burden of saving everything all at once. We find the freedom to act with purpose but without panic, to care deeply without being crushed by the weight of caring.

The peace that comes from expanded horizon isn't the peace of apathy or denial. It's the profound tranquility that philosopher Spinoza described as arising "not because we don't know or don't feel our problems, but because we understand their place in a larger whole." It's what poet Wendell Berry captures in his counsel to "Be joyful though you have considered all the facts." This paradoxical capacity—to fully acknowledge reality's pain while maintaining inner equilibrium—becomes accessible when we expand our temporal vision.

And perhaps most precious of all, we discover that the wisdom we need most desperately has already been preserved for us by those who weathered their own storms—fortresses of the spirit tested by time and found reliable. They remind us that our anxiety, our sense of standing at history's precipice, our fear that everything good might be lost, are themselves timeless human experiences. And in recognizing this, we find both comfort and courage to face whatever comes.

The lighthouse keeper returns to his post as night falls again. There will be other storms, other moments when the horizon disappears and his world contracts to the small circle of light he tends. But he will remember what he has seen—the constellation of lights stretching far beyond his own tower, the continuity of human effort across time. And that memory will grant him peace amid whatever tempests the future brings.

So too for us. By looking both backward and forward, we expand our present moment into something larger and more meaningful. We find our place in humanity's ongoing story.

And in doing so, we discover the peace that comes not from escaping the storm, but from understanding our role within and beyond it—a peace that enables us to act with both courage and wisdom in the face of whatever challenges we are called to address.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider subscribing or sharing it.

References and Further Reading

Quotes and References

The opening quote from Eric Greitens comes from his book Resilience: Hard-Won Wisdom for Living a Better Life, which explores how ancient philosophical traditions can help us navigate modern challenges. Rob Fitzpatrick suggests that books can be measured by their valuable insight per page ratio. Resilience has one of the highest ratios of any book I’ve read, and is a book I return to often.

Chuck Klosterman's observation about the provisional nature of present truth is from But What If We're Wrong: Thinking About the Present As If It Were the Past, a fascinating exploration of how future generations might view our certainties.

Marcus Aurelius' quote "You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength" comes from his Meditations. I suggest picking up Gregory Hays’ translation if you haven’t read this yet.

Seneca's insights about suffering in imagination and distinguishing between what we can and cannot control appear in his Letters from a Stoic, particularly Letters 13 and 24, written during his exile and final years under Nero's increasingly tyrannical rule.

The concept of "amor fati" (love of fate) was central to Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy, particularly in works such as The Gay Science and Ecce Homo.

Rilke's advice to "Live the questions now" comes from Letters to a Young Poet, a collection of ten letters written to Franz Xaver Kappus between 1902 and 1908.

Viktor Frankl's observation about changing ourselves when we cannot change our situation is from Man's Search for Meaning, written after his experiences in Nazi concentration camps.

Van Gogh's quote about the stars comes from a letter to his brother Theo, written in 1888 while he was in the asylum at Saint-Rémy.

Bessel van der Kolk's insight about safety and connection is from The Body Keeps the Score, his seminal work on trauma and recovery.

James Baldwin's observation about facing problems appears in "As Much Truth As One Can Bear," published in The New York Times Book Review, January 14, 1962.

Joanna Macy's concept of "active hope" is explored fully in her book Active Hope: How to Face the Mess We're in without Going Crazy, co-authored with Chris Johnstone.

Reinhold Niebuhr's "Serenity Prayer" has been widely adopted, though its precise origins are debated. Evidence suggests it was written between 1932-1934.

Václav Havel's distinction between hope and optimism appears in Disturbing the Peace, conversations with Karel Hvížďala.

Rabbi Tarfon's wisdom appears in Pirkei Avot (Ethics of the Fathers) 2:16, a collection of ethical teachings compiled in the Mishnaic period (roughly 10-220 CE).

Spinoza's insight about understanding problems in a larger context derives from his Ethics (1677), particularly Part V, which explores human freedom and the intellectual love of God/Nature.

Wendell Berry's counsel to "Be joyful though you have considered all the facts" comes from his poem "Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front," originally published in The Country of Marriage.

Additional Perspectives

For those interested in how historical perspective shapes our understanding of present crises, I recommend David Christian's Origin Story: A Big History of Everything, which places current human challenges within the vast context of cosmic evolution.

Rebecca Solnit's Hope in the Dark offers a nuanced exploration of how social movements create change over time, often in ways that aren't immediately visible to those living through them.

For a neurological perspective on how our brains process time and meaning, I recommend Dean Buonomano's Your Brain Is a Time Machine. It explores how our perception of time shapes our experience of reality in ways we rarely consider.

For a fascinating examination of how past societies faced existential threats, Jared Diamond's Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Succeed provides case studies of both successful and unsuccessful responses to environmental and social challenges.

Martin Seligman's Learned Optimism explores the psychological mechanisms behind resilience and how we can cultivate more adaptive responses to adversity through cognitive reframing techniques.

For those drawn to the integration of spiritual and psychological perspectives on finding peace amid chaos, Pema Chödrön's When Things Fall Apart offers practical wisdom from the Buddhist tradition that complements many of the Western perspectives mentioned in this essay.