Fighting for Nothing While Everything Is at Stake

Winning a conflict depends on purpose clarity just as much as tactics

This essay is part five of my ongoing investigation into the principles that shape conflict. Each essay can be read on it’s own, or you can read parts one, two, three, and four first.

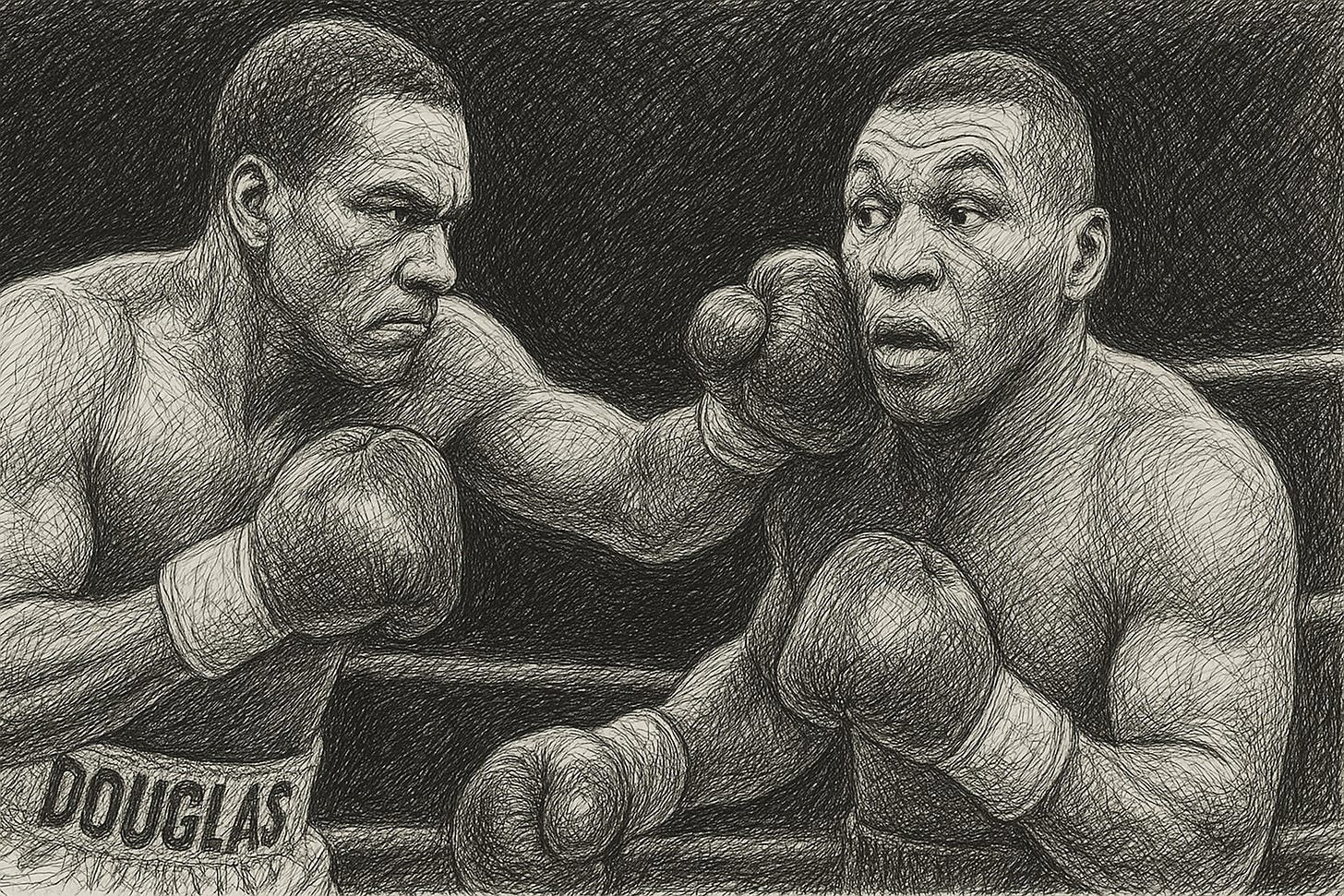

The atmosphere at the Tokyo Dome on February 11, 1990, carried the weight of inevitability. Mike Tyson, the undisputed heavyweight champion of the world, made his way through the tunnel toward the ring with the mechanical precision that had characterized his approach to boxing for months. At twenty-three, he remained undefeated across thirty-seven professional fights, a destroyer of men who had systematically dismantled every challenger placed before him. The boxing establishment had crowned him invincible—a force of nature that transcended sport itself.

His opponent that night, James "Buster" Douglas, entered as such a profound underdog that Las Vegas oddsmakers had set the line at 42-to-1 against him. Most observers couldn't recall his last significant victory. Sports Illustrated hadn't bothered to send their primary boxing writer to cover what everyone assumed would be another inevitable Tyson demolition. The fight existed merely to satisfy contractual obligations before Tyson moved on to more lucrative encounters.

Yet as these two men stepped into the squared circle that February night, an invisible but decisive battle had already been waged—one that would determine the outcome more than any combination of punches, defensive techniques, or athletic conditioning. It was a battle fought in the realm of purpose, and Mike Tyson had already lost it.

In the months preceding the fight, Tyson's life had descended into chaos that would have been unthinkable during his rise under the tutelage of Cus D'Amato. His marriage to actress Robin Givens had disintegrated amid public humiliation. His mentor D'Amato, the philosophical architect of his boxing greatness, had died three years earlier, leaving Tyson adrift without the disciplinary structure that had channeled his rage into excellence. The young champion had become intoxicated by celebrity culture, spending more time at nightclubs than in training facilities.

Most critically, Tyson had lost sight of what he was fighting for. The hunger that had driven him from the streets of Brownsville to heavyweight supremacy had been replaced by expectation—the assumption that his fearsome reputation would intimidate opponents into submission. He entered the ring that night not to prove his dominance or defend his championship with purpose, but merely to collect a paycheck and maintain an illusion of invincibility.

Douglas, meanwhile, carried a weight of purpose so profound it transformed his very being. Just twenty-three days before the fight, his mother Lula Pearl had died unexpectedly, leaving behind a promise that Douglas had made to her—that he would become heavyweight champion of the world. Every punch he threw in that Tokyo ring served this singular, unshakeable objective. He had transformed personal grief into crystalline clarity.

When Douglas landed the devastating combination that sent Tyson crashing to the canvas in the tenth round—the first time the champion had ever been knocked down—the boxing world witnessed more than an upset. They observed the inevitable result of a fundamental principle: when two forces of relatively equal capability collide, victory belongs to the one with clearer purpose.

The Fog of Engagement

This principle extends far beyond athletics into every domain of human conflict. As Carl von Clausewitz observed, "War is merely the continuation of politics by other means." The Prussian master understood that military tactics without clear political objectives inevitably lead to what I explored in my examination of pyrrhic victories—triumphs so costly they might as well be defeats.

Yet most people enter their daily battles—negotiations at work, disagreements with family members, competitive situations—without the crystalline purpose that would transform their approach to engagement itself. They become lost in the fog of engagement, to borrow another phrase from Clausewitz, where the emotional intensity of conflict obscures the original objectives that made the battle worthwhile.

"In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer," wrote Albert Camus, capturing something essential about how clarity of purpose can sustain us through challenging encounters. This invincible summer—this core sense of what we're truly fighting for—remains elusive to most people once the heat of conflict begins.

Marcus Aurelius grasped this challenge intimately. Writing in his Meditations while managing an empire beset by plague and invasion, the Stoic emperor observed, "You have power over your mind—not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength." His insight penetrates to the heart of human conflict: the most important battle occurs not against external opponents but within ourselves—the struggle to maintain focus on what actually matters rather than being swept away by immediate emotional demands.

Consider the parent who begins disciplining a child to teach responsibility but gradually shifts into a power struggle about authority itself. The original purpose—cultivating maturity and self-direction—gives way to ego-driven objectives that serve no constructive end. The marriage that deteriorates because both partners become more invested in winning arguments than nurturing connection. The workplace that becomes toxic because colleagues prioritize being right over solving problems.

This phenomenon, known as purpose drift, represents one of the most common causes of conflict failure. We enter engagements with legitimate objectives but allow the emotional intensity of the moment to redirect our energy toward goals that feel satisfying in the heat of battle but ultimately undermine our deeper interests. Like Tyson in that Tokyo ring, we begin fighting for one thing but end up fighting for something else entirely—or for nothing meaningful at all.

The Paradox of Strategic Restraint

Yet understanding this dynamic reveals a paradox that connects directly to my exploration of invisible victories: often, the clearest purpose leads not to more intense fighting but to more thoughtful engagement that achieves objectives with minimal collateral damage. As Sun Tzu observed, "The best victory is when the opponent surrenders of its own accord before there are any actual hostilities."

This wisdom echoes through history's most masterful responses to conflict. When pressure mounts and stakes feel highest, those who maintain connection to their deeper purposes often find paths that seem counterintuitive yet prove devastatingly effective.

We can see a prime example of this in recent cultural history. When Oprah Winfrey faced intense backlash in early 2020 for endorsing "American Dirt," a novel that Latino communities criticized for perpetuating harmful stereotypes, she confronted the kind of crisis that destroys careers and reputations. Critics organized boycotts, protests erupted, and her cultural authority faced unprecedented challenge from communities whose voices she had long championed.

Most public figures in such circumstances follow predictable patterns: they either double down defensively or issue generic apologies designed to minimize damage. Both approaches prioritize immediate reputation management over deeper objectives—the kind of purely reactive thinking that Clausewitz warned against.

Winfrey chose a path that seemed to surrender territory yet ultimately claimed higher ground. She paused, reconnected with her fundamental purpose—using her platform to elevate important voices and facilitate meaningful conversations—and decided to face the controversy head-on. "I have become distinctly aware that there is a need for a more thoughtful discussion around 'American Dirt,'" she wrote. She invited the book’s author, along with several of its critics, to join her for a televised discussion of the book’s themes and influence.

This response embodied what Lao Tzu called "wu wei"—purposeful action that accomplishes more through thoughtful engagement than aggressive defense. Rather than dismissing critics, Winfrey created space for the very conversations that her platform was designed to facilitate. The controversy faded, her credibility deepened rather than diminished, and she continued building the platform that had always been her true objective. By stepping toward the tension rather than away from it, she transformed potential opposition into collaborative dialogue. Her approach demonstrated what Lao Tzu understood: like water reshaping stone through patient persistence, purpose-driven engagement often achieves what aggressive defense cannot.

The Alchemy of Clear Intention

This paradox reveals something deeper about the nature of purposeful engagement: clarity about what you're truly fighting for transforms not just how you approach conflict but which conflicts you choose to engage at all. As I explored in my analysis of choosing battles wisely, the masters of human conflict understand that most battles are won or lost before they begin—in the realm of preparation and purpose rather than technique and immediate response.

"If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles," Sun Tzu taught. But his deeper insight lies in recognizing that knowing yourself—understanding your true objectives and the motivation behind them—often proves more challenging than understanding your opponent's position. We can spend years studying external circumstances while remaining strangers to our own deepest intentions.

When we possess genuine clarity about our fundamental purposes, something remarkable occurs: apparent obstacles begin to reveal themselves as opportunities, and seemingly impossible situations disclose unexpected pathways forward. This transformation happens because clear purpose operates like a lens, bringing into focus possibilities that remain invisible to those caught in the fog of immediate concerns.

The parent who understands that their true objective is raising a thoughtful, responsible adult can distinguish between moments that require firm boundaries and those that call for patient explanation. The manager who grasps that their fundamental goal is cultivating excellence can separate constructive feedback from ego-driven correction. The spouse who remembers that their deepest desire is nurturing partnership can recognize when being right matters less than being connected.

The alchemy occurs when we stop asking "How can I win this argument?" and begin asking "What outcome would actually serve my deeper purposes?" This shift in questioning often reveals that the most direct path to our objectives lies not through confrontation but around it—not by defeating opposition but by making opposition irrelevant.

The Discipline of Inner Clarity

Yet this clarity doesn't emerge automatically in the heat of conflict. By then, emotions are running high, and the kind of clear thinking required for wise decision-making becomes nearly impossible. Most successful people develop purpose clarity as a daily discipline. This requires honest self-examination that goes deeper than surface reactions. At the end of each day, identify one challenge or conflict you faced and ask yourself: "What was I really trying to accomplish, and did my approach serve that deeper objective?"

Often, this reflection reveals disconnects between surface goals and fundamental purposes. You might discover that your argument with a colleague was less about the specific policy disagreement and more about feeling heard and respected in your professional environment. Or that your frustration with a family member's behavior stemmed not from their actions themselves but from anxiety about your ability to influence situations that matter to your long-term well-being.

This kind of self-examination builds self awareness—the ability to understand not just what's happening around you but how those events relate to your broader life purposes. In conflict situations, this translates to recognizing when you're drifting from your true objectives and course-correcting before significant damage occurs to relationships or long-term interests.

The practice also cultivates what the Greeks called "phronesis"—practical wisdom that enables appropriate action in particular circumstances. Unlike technical knowledge, which applies universal principles, this wisdom emerges from the patient integration of experience, reflection, and moral clarity about what matters most. As I explored in my examination of wisdom and patience, such understanding cannot be rushed but develops through sustained attention to the deeper patterns of our lives.

The Architecture of Enduring Victory

This discipline of inner clarity ultimately serves a larger purpose: creating the conditions for victories that endure rather than pyrrhic triumphs that cost more than they're worth. As I explored in my examination of which conflicts deserve our full engagement, the battles worth fighting are those that serve purposes larger than immediate ego satisfaction or momentary advantage.

"The supreme excellence consists of breaking the enemy's resistance without fighting," Sun Tzu taught, but his deeper insight concerned the nature of victory itself. The greatest triumph in any conflict isn't defeating your opponent—it's achieving your purpose with minimal necessary cost to relationships, resources, and future possibilities.

Sometimes this requires fighting with greater intensity than you initially planned. Sometimes it requires restraint that others mistake for weakness. Always, it demands the courage to remain true to what actually matters, even when circumstances or emotions pull you toward easier but ultimately self-defeating responses.

This understanding carries profound implications for how we think about success over time. The victories that matter most aren't those that feel most satisfying in the moment but those that compound over years and decades, building toward the kind of life we actually want to live. Mike Tyson's early career demonstrated the power of purpose-driven preparation—every training session, every sacrifice, every disciplined choice served his larger objective of championship excellence. But when he lost connection to that deeper purpose, his formidable skills became merely mechanical, impressive but ultimately hollow.

Buster Douglas, in contrast, transformed personal loss into unwavering clarity about what his victory would mean—not just for himself but for the memory of his mother and the promise he had made to her. This connection between present action and deeper meaning enabled him to fight with a conviction that no amount of technical skill could match.

The same dynamics operate in every domain of human engagement. In your own conflicts—whether they unfold in boardrooms or family rooms, in professional negotiations or personal relationships—the fundamental question remains: Are you fighting with the mechanical precision of purposeless technique, relying on habit and expectation? Or are you engaging with the clarity that comes from understanding what truly matters and why?

The choice isn't made once, in some moment of crisis, but daily, through the small decisions that build character and the quiet reflections that keep you connected to purposes larger than immediate comfort. Master this invisible dimension of conflict, and you'll discover what the greatest masters have always known: the most dangerous opponent is not the one with superior technique but the one who remembers what they're truly fighting for.

The path toward genuine mastery begins not with studying tactics or developing rhetorical skills, but with the patient work of understanding what you're really trying to accomplish—and why it matters enough to engage at all. In a world filled with unnecessary battles, this clarity becomes both shield and sword, protecting you from futile engagements while sharpening your effectiveness in conflicts that truly matter for the long sweep of your life.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this essay, please consider sharing it.

References and Further Reading

Quotes and References

The Tyson-Douglas fight details come from contemporary accounts, including the documentary "42 to 1." Douglas's mother Lula Pearl died on January 18, 1990, just 23 days before the fight at the Tokyo Dome. The 42-to-1 odds reflected not just Tyson's dominance but the boxing establishment's inability to recognize how purpose can transform athletic performance.

Carl von Clausewitz's observation that "war is merely the continuation of politics by other means" appears in Book 1, Chapter 1 of On War (1832). His broader framework emphasizing political objectives over military tactics revolutionized understanding of conflict and applies equally to engagements far removed from battlefield conditions.

Albert Camus wrote "In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer" in "Return to Tipasa," part of his collection Summer (L'Été) (1954).

Marcus Aurelius composed his Meditations while campaigning along the Danube frontier, facing both military threats and the Antonine Plague.

Sun Tzu's insights come from The Art of War, written in the 5th century BCE. His emphasis on knowing yourself and your enemy (Chapter 3) and achieving victory without fighting (Chapter 2) established principles that remain foundational to understanding conflict across all domains of human experience.

Lao Tzu's observation about water overcoming the hard and strong appears in the Tao Te Ching. His concept of "wu wei" (effortless action) provides a framework for understanding how restraint guided by clear purpose can achieve objectives that aggressive intervention cannot.

Oprah Winfrey's response to the "American Dirt" controversy occurred in January 2020.

Additional Perspectives

For those interested in how ancient wisdom applies to modern conflict, Pierre Hadot's Philosophy as a Way of Life explores how classical philosophers developed practical exercises for maintaining clarity under pressure.

William Ury's Getting to Yes with Yourself offers contemporary insights into the internal negotiations that must precede external conflict resolution. His emphasis on understanding your own interests and motivations before engaging others complements the classical wisdom explored in this essay.

Ryan Holiday's The Obstacle Is the Way provides accessible applications of Stoic principles to modern challenges, particularly relevant for understanding how purpose clarity can transform apparent setbacks into foundations for more enduring success.

Barbara Tuchman's The March of Folly examines historical examples of leaders who lost sight of their fundamental objectives, leading to catastrophic defeats despite apparent advantages. Her analysis illuminates the cognitive patterns that cause purpose drift and its consequences across centuries of human conflict.

Carl Jung's exploration of "holding the tension" in difficult situations offers psychological insight into why most people lose clarity under pressure and how exceptional individuals maintain focus on deeper purposes despite emotional intensity and external chaos.

For readers interested in the neuroscience of decision-making under pressure, Antonio Damasio's Descartes' Error explores how emotion and reason interact in wise decision-making, providing scientific context for ancient insights about maintaining clarity during conflict and challenge.